Yip Man, who introduced wing chun to the west, was from the south of China where Cantonese language is spoken. Additionally, the Chinese pronunciation is very different from the Western pronunciation and that is why people misunderstand it. Consequently, we do not have only Wing Chun, but also Ving Tsun, Ving Chun, and Wing Tsun, as well as some styles that at the end of Wing Chun as a third word add Kuen (Mandarin Quan), meaning “series of fist boxing”.

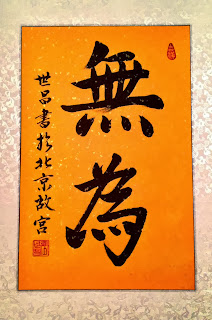

Wing chun is also based on the Yin and Yang principle, meaning soft and hard or motion and stillness, attack and defense—they all come from each other. Yin and Yang may be the most important theory in China. The concept of Yin and Yang is simple and at the same time vast in nature. The earliest origin of Yin and Yang must have come from the observation of day turning into night and night turning into day. Yin and Yang are interdependent on each other. Yin cannot survive without Yang and vice versa—there cannot be activity without rest and rest without activity. Which is the fundamental tenet in Chinese thought that has been emphasized mostly by the Daoist schools is wu wei. The literal meaning of wu wei is ‘without action’ and is often included in the paradox wei wu wei, ‘action without action’ or ‘effortless doing.’ It means natural action—as planets revolve around the sun, they ‘do’ this revolving, but without ‘doing’ it, or as a tree grows, it ‘does,’ but without ‘doing.’ Wu wei refers to behavior that arises from a sense of oneself as connected to others and to one’s environment. It is not motivated by a sense of separateness. It is action that is spontaneous and effortless. If wu wei is seen purely as inactivity, then indeed it is anachronistic in todays’ times. But wu wei is not just a lack of purposeful action, it involves knowing when to act and when not to act. Therefore, it is a state of alert quietude and watchfulness, it is action only when and where required to restore the balance of universal harmony. In Wing Chun, one utilizes all these principles when fighting.

Wing chun is also based on the Yin and Yang principle, meaning soft and hard or motion and stillness, attack and defense—they all come from each other. Yin and Yang may be the most important theory in China. The concept of Yin and Yang is simple and at the same time vast in nature. The earliest origin of Yin and Yang must have come from the observation of day turning into night and night turning into day. Yin and Yang are interdependent on each other. Yin cannot survive without Yang and vice versa—there cannot be activity without rest and rest without activity. Which is the fundamental tenet in Chinese thought that has been emphasized mostly by the Daoist schools is wu wei. The literal meaning of wu wei is ‘without action’ and is often included in the paradox wei wu wei, ‘action without action’ or ‘effortless doing.’ It means natural action—as planets revolve around the sun, they ‘do’ this revolving, but without ‘doing’ it, or as a tree grows, it ‘does,’ but without ‘doing.’ Wu wei refers to behavior that arises from a sense of oneself as connected to others and to one’s environment. It is not motivated by a sense of separateness. It is action that is spontaneous and effortless. If wu wei is seen purely as inactivity, then indeed it is anachronistic in todays’ times. But wu wei is not just a lack of purposeful action, it involves knowing when to act and when not to act. Therefore, it is a state of alert quietude and watchfulness, it is action only when and where required to restore the balance of universal harmony. In Wing Chun, one utilizes all these principles when fighting.

Wing chun develops the ability to use any part of a body to strike and protect with the fingers, hands, elbows, knees, head, feet, shoulders, hip. These tools are used naturally according to the situation and the task at hand. What is important is that one learns the cultivated skill of striking vital areas of the opponent’s body. This ability increases the effectiveness of the strikes, which distinguishes Wing chun from other styles by using a highly skillful art rather than a brutish clash of force against force used in some other styles.

They are qualities to be sought not just in the body, but also in the mind and spirit. It is an attitude that is confident, assured, and concentrated, yet open to new ideas. It is Wing chun goal and worth cultivating. And the same applies in leadership.

In order to reach those deeper levels, one must begin speaking of sensitivity, of balance and harmony, of interconnectedness and attitude, of positivity and ethics, and of moral action, and also one must not forget healing. Therefore, in Wing chun one trains soft and hard to discover sensitivity and, because of stress, discover a strength. Isn't leadership dealing with the same topics?

Wing Chun is therefore a value-driven system. This definitively matches a leadership process too. One should understand a deep meaning of this, whether through protecting oneself or others or in competition. One should always strive to be in harmony with nature to increase self-understanding and lastly to master fears. Fears that we are aware of, fears we have while in a leadership process, and more.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.