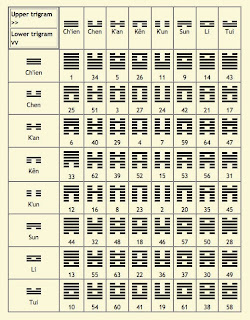

I Ching is built of linear signs represented by 64 sets composed of two three-line arrangements, namely hexagrams (guà) that represent sixty four main kinds of life situations. The lines of hexagram are, of course, not just lines. Each hexagram has a name and is a physical symbol representing deeply metaphysical or subconscious manifestation. Every line of hexagram can be broken or unbroken. The unbroken or solid line represents yang, the ‘creative’ principle. The broken or open line with a gap in the centre represents yin, the ‘receptive’ principle. These principles are also represented in a common circular symbol or diagram known as Tai Chi Tú but more commonly known in the West as the yin-yang symbol, expressing the idea of wholeness of constantly undergoing change.

Traditionally the I Ching is consulted by throwing 50 yarrow stalks, but today a set of three coins is used more frequently. When a hexagram is cast using one of the traditional processes of divination with I Ching, each yin and yang line will be indicated as either moving (changing), or fixed (unchanging). A second hexagram is created by changing moving lines to their opposite and represents new possibilities and transition that might occur due to someone’s interaction of a free will.

Traditionally the I Ching is consulted by throwing 50 yarrow stalks, but today a set of three coins is used more frequently. When a hexagram is cast using one of the traditional processes of divination with I Ching, each yin and yang line will be indicated as either moving (changing), or fixed (unchanging). A second hexagram is created by changing moving lines to their opposite and represents new possibilities and transition that might occur due to someone’s interaction of a free will.